Table of Contents

- Course outline

- I. Lectures

- 1. History: How did we get Hebrews?

- 2. Canon: Should we accept Hebrews?

- 3. Circumstances: The author, audience, date and destination of Hebrews

- 4. Strategy: Why is Hebrews written like it is?

- 5. Sources: Where did the content come from?

- 6. Theology: What does Hebrews say about God?

- 7. Christology: What does Hebrews say about Christ?

- 8. Covenants and priests: What does Hebrews say about the Old and New Testaments and the role of human mediators?

- II. Exegesis

- References

List of Figures

- 1.1. Christian population vs date

- 1.2. Codex capacity vs date

- 1.3. Textual map

- 1.4. Spelling map

List of Tables

- 1. Sessions

- 2. Texts, lectures and seminars

- 3. Useful websites

- 4. Grades

- 5. NT422 assessment

- 6. NT432 assessment

- 7. NT622 assessment

- 8. NT632 assessment

- 9. Tutorial assessment

- 10. Sermon or Bible study assessment

- 11. Translation assessment

- 12. Book review assessment

- 13. Exegesis paper assessment

- 1.1. Number of MSS vs date

- 1.2. Codex capacity vs date

- 9.1. Alternation of exposition and exhortation

- 9.2. God has spoken...

- 10.1. Alternation of exposition and exhortation

- 10.2. God has spoken...

- 11.1. Psalm numbering in the MT and LXX

- 11.2. Cosmic hierarchy

- 16.1. Vanhoye's analysis of Hebrews

Table of Contents

Three components of the assessment for each student require written submissions. Students doing seminars or sermon / Bible studies are required to distribute an outline the week before the due date and to do a five minute presentation on the due date. Those doing a book review are required to distribute an outline at seminar 6 (Mar 31) and to do a five minute presentation and share leadership on the due date (seminar 8, Apr 28).

Note

TBA = a TLA (three letter acronym) meaning “to be advised.” Please advise me ASAP (as soon as possible).

This is a thirteen week course on the Epistle to the Hebrews delivered at the Baptist Theological College (Western Australia) in the first semester of 2005.

The syllabus is comprised of three components:

- Part 1

An introduction to Hebrews including questions of authorship, date, destination, etc.

- Part 2

The theology of the epistle, including such themes as the old and new covenants, sacrifice, perfection, the use of the Old Testament, the cross and ascension.

- Part 3

NT422/622: Exegesis of the English text of Hebrews 1-13; NT 432/632: Exegesis of the Greek text of Hebrews 1-8, 12.

By the end of this unit, students should be:

familiar with the introductory issues covered in part 1

familiar with the theological issues covered in part 2

better able to analyse, understand and explain what Hebrews says, why it says so, and what difference it makes.

The lecturer is Tim Finney, a former student of BTC (WA).

The course is divided into thirteen weeks, with each week comprised of four sessions. The first session is a Greek tutorial and attendance is only required for those taking the Greek option. All students are required to attend the second, third and fourth sessions.

Table 1. Sessions

| Session | Times | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Thur 5.40 - 6.20 pm | Greek tutorial |

| 2 | Thur 6.30 - 7.10 pm | Exegesis |

| 3 | Thur 7.20 - 8.00 pm | Lecture |

| 4 | Thur 8.20 - 9.00 pm | Seminar |

Lectures and seminars cover introductory and theological components (i.e. parts 1 and 2). The lecture and seminar topics for each week are listed in the schedule, below. Each seminar (apart from seminars 6 and 8, which are for NT622 and NT632 students) covers an aspect of the subject addressed in the preceding lecture, and takes the form of either a tutorial or class discussion. If a student is allocated a particular week's seminar topic, he or she will deliver a tutorial that week. If no student chooses a particular week's seminar topic then there will be a class discussion on the matter instead.

Greek tutorial and exegesis sessions cover the exegesis component (i.e. part 3). The text has been divided into consecutive passages for use in these sessions, and the passage for each week is given in the schedule, below. The same passage of text is covered in the Greek tutorial and exegesis sessions for a particular week. Students are allocated passages from the schedule for sermon, Bible study, exegesis and Greek translation assignments.

Table 2. Texts, lectures and seminars

| Date | Text | Lecture | Seminar |

|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1: Feb 24 | Heb 1.1-2.4 | Lecture 1 | Seminar 1 |

| Week 2: Mar 3 | Heb 2.5-2.18 | Lecture 2 | Seminar 2 |

| Week 3: Mar 10 | Heb 3.1-4.16 | Lecture 3 | Seminar 3 |

| Week 4: Mar 17 | Heb 5.1-5.10 | Lecture 4 | Seminar 4 |

| Week 5: Mar 24 | Heb 5.11-6.20 | Lecture 5 | Seminar 5 |

| Week 6: Mar 31 | Heb 7.1-7.28 | Lecture 6 | Seminar 6 |

| Week 7: Apr 7 | Heb 8.1-8.13 | Lecture 7 | Seminar 7 |

| Non-teaching (2 weeks) | |||

| Week 8: Apr 28 | Heb 9.1-9.28 | Lecture 8 | Seminar 8 |

| Week 9: May 5 | Heb 10.1-10.18 | Lecture 9 | Seminar 9 |

| Week 10: May 12 | Heb 10.19-10.39 | Lecture 10 | Seminar 10 |

| Week 11: May 19 | Heb 11.1-11.40 | Lecture 11 | Seminar 11 |

| Week 12: May 26 | Heb 12.1-12.29 | Lecture 12 | Seminar 12 |

| Week 13: June 2 | Heb 13.1-13.25 | Lecture 13 | Seminar 13 |

- Lecture 1

Introduction: course outline; how to do written assignments; allocation of exegesis assignments

- Lecture 2

History: How did we get Hebrews? (Transmission, textual issues, integrity, unity)

- Lecture 3

Canon: Should we accept Hebrews?

- Lecture 4

Circumstances: The author, audience, date and destination of Hebrews

- Lecture 5

Strategy: Why is Hebrews written like it is? (Genre, rhetoric, structure, style)

- Lecture 6

Sources: Where did the content come from? (Old Testament quotations; New Testament parallels; Jewish philosophy; Greek philosophy; Early Christian philosophy)

- Lecture 7

Theology: What does Hebrews say about God?

- Lecture 8

Christology: What does Hebrews say about Christ?

- Lecture 9

Covenants and priests: What does Hebrews say about the Old and New Testaments and the role of human mediators?

- Lecture 10

Soteriology: What does Hebrews say about salvation and perseverance?

- Lecture 11

Ecclesiology: What does Hebrews say about the church?

- Lecture 12

Cosmology and eschatology: What does Hebrews say about life, the universe, and everything?

- Lecture 13

Conclusion: What does Hebrews say, why does it say so, and what difference does it make?

- Seminar 1

Introduction: How to do tutorials; how to do class discussions; allocation of tutorials

- Seminar 2

What is the text of the New Testament? How do you deal with textual variation? How do you explain the phenomenon to others?

- Seminar 3

When should a work be accepted as scripture? What should we do with scripture?

- Seminar 4

What kind of person wrote Hebrews? Develop an evidence-based profile of the author including name, address, birthdate, convictions, education and nationality.

- Seminar 5

How do you persuade people? What methods are used in Hebrews? What methods are popular today? Which methods are legitimate?

- Seminar 6

NT622 and NT632 seminar (others may audit if they wish): Discuss issues raised to date through reading and course work.

- Seminar 7

What does Hebrews say about the Holy Spirit? What about the baptism of the Holy Spirit?

- Seminar 8

NT622 and NT632 seminar (others may audit if they wish): Presentation and discussion of book reviews.

- Seminar 9

What kinds of priests does Hebrews allow under the new covenant? What are their qualifications? Does the church take any notice of Hebrews in this regard? If not, why not?

- Seminar 10

What does Hebrews say about the eternal security of the believer? How can we avoid apostasy?

- Seminar 11

What are the rules for Christian living according to Hebrews? Do we do this? If not, why not?

- Seminar 12

According to Hebrews, how was the universe created, how is it sustained, and how will it end up? Is this consistent with the rest of the New Testament? Is this consistent with current scientific thought?

- Seminar 13

What difference does Hebrews make to you?

The following commentaries have been placed on closed reserve in the library. You are required to identify and read the relevant parts of at least one of the commentaries prior to each week's sessions. (Make sure that you read up on the week's exegesis text and the lecture subject.) There is no need to stick to the same commentary from week to week.

All students

deSilva, David A. Perseverance in Gratitude: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on the Epistle "to the Hebrews". Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 2000.

Ellingworth, Paul. The Epistle to the Hebrews: A Commentary on the Greek Text. New International Greek Testament Commentary. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 1993.

Supplementary commentary for Greek option

Note

The Translator's Handbook is a supplementary text; student's taking the Greek option should use the other commentaries as well.

Apart from the Bible, students are not required to have any books or a reader for this course.

Whether or not you wish to purchase a book on Hebrews is up to you. By the end of the course you will know the literature a lot better.

I have a copy of Turabian, which I find a very helpful style guide for written work. It specifies correct practice for abbreviation, numbers, capitalization, quotations, tables, notes and bibliographies:

Its method of presentation for bibliographies differs slightly from that specified in the BTC Guide to the Presentation of Essays. Nevertheless, I recommend it as a widely accepted standard guide, and you will not be penalised for following its conventions provided that you are consistent.

A useful list of Turabian-style citations is provided at http://www.lib.usm.edu/research/guides/turabian.html.

The Student Handbook includes a list of some useful sites, mainly "gateways". Some more useful ones are listed below:

Table 3. Useful websites

| URL | Comment |

|---|---|

| www.greekbible.com | Has Greek text, meanings and grammatical analysis of individual words. Enter a verse to get the text, then click on a word to get the meaning and grammatical analysis. |

As mentioned before, all students are required to attend the exegesis, lecture and seminar sessions, while students taking the Greek option are required to attend the Greek tutorials as well.

All assignments must be completed and an overall result of 50% must be achieved to pass the unit. A result of at least 40% is required in each component worth more than 20% of the total.

Work submitted after the due date will be penalised unless an extension has been granted by the lecturer. You need a good reason to be granted an extension; "I left it too late" is not a good reason.

All components of the unit are assessed by the lecturer. Copies of the exegesis papers will be sent to an ACT moderator to assess the level of marking.

Written submissions should conform to the BTC Guide to the Presentation of Essays, which incorporates ACT requirements. Please note carefully the statements against plagiarism, collusion, cheating and discriminatory language.

The BTC uses the ACT marking scale, with results given as letter grades. The BTC Student Handbook gives the learning outcomes corresponding to each result.

Table 4. Grades

| Result | Meaning | Range (%) |

|---|---|---|

| F | Fail | 0-49 |

| P | Pass | 50-57 |

| P+ | Pass plus | 58-64 |

| C | Credit | 65-72 |

| D | Distinction | 73-79 |

| HD | High distinction | 80-100 |

Individual units are assessed as follows:

Table 5. NT422 assessment

| Component | Extent | Due date | Percentage | Syllabus component(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tutorial paper | 1500 words | On the day the relevant topic is scheduled. (Outline required the week before.) | 25 | Part 1 or 2 |

| Sermon / Bible study | 1500 words | On the day the relevant passage is scheduled. (Outline required the week before.) | 25 | Part 3 |

| Exegesis paper | 3000 words | Thursday, 2 June 2005 | 40 | Part 3 |

| Class participation | All required sessions | All required sessions | 10 | Parts 1-3 |

Note

No two written assignments covering part 3 of the syllabus may be based on the same material.

Table 6. NT432 assessment

| Component | Extent | Due date | Percentage | Syllabus component(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tutorial paper | 1500 words | On the day the relevant topic is scheduled. (Outline required the week before.) | 25 | Part 1 or 2 |

| Translation of Greek text | Three passages, 1500 words | Thursday, 28 April 2005 | 25 | Part 3 |

| Exegesis paper | 3000 words | Thursday, 2 June 2005 | 40 | Part 3 |

| Class participation | All required sessions | All required sessions | 10 | Parts 1-3 |

Note

No two written assignments covering part 3 of the syllabus may be based on the same material.

Table 7. NT622 assessment

| Component | Extent | Due date | Percentage | Syllabus component(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tutorial paper | 2000 words | On the day the relevant topic is scheduled. (Outline required the week before.) | 25 | Part 1 or 2 |

| Book review | 2000 words | Thursday, 28 April 2005 | 25 | Varies depending on the book |

| Exegesis paper | 3000 words | Thursday, 2 June 2005 | 40 | Parts 2 and 3 |

| Class participation | All required sessions | All required sessions | 10 | Parts 1-3 |

Note

No two written assignments covering parts 2 or 3 of the syllabus may be based on the same material.

Table 8. NT632 assessment

| Component | Extent | Due date | Percentage | Syllabus component(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Translation of Greek text | Four passages, 2000 words | Thursday, 28 April 2005 | 25 | Part 3 |

| Book review | 2000 words | Thursday, 28 April 2005 | 25 | Varies depending on the book |

| Exegesis paper | 3000 words | Thursday, 2 June 2005 | 40 | Parts 2 and 3 |

| Class participation | All required sessions | All required sessions | 10 | Parts 1-3 |

Note

No two written assignments covering parts 2 or 3 of the syllabus may be based on the same material.

Each student required to present a tutorial is allocated one of the seminar topics listed above. An outline of the tutorial paper which includes a bibliography and discussion questions is required to be distributed one week prior to the tutorial date.

All students are required to read about the seminar topic as part of their preparation for the week's sessions. Putting effort into this aspect is bound to make the tutorial more lively.

The student giving the tutorial will make a presentation and lead the seminar for the relevant session. About half of the session should be reserved for the class discussion. I encourage you to be creative in your presentation and leadership. (E.g. Divide the class into two and let them fight it out on some contentious issue. This is just an example -- think up your own.)

The tutorial paper must:

address all parts of the seminar topic

make use of the biblical text and reference works such as commentaries, monographs and journal articles

contain a select bibliography of references you have consulted and found useful.

Marks will be allocated as follows:

Table 9. Tutorial assessment

| Component | Extent | Due date | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outline | About one page | One week prior to tutorial | 10 |

| Paper | 1500 (NT422, NT432) or 2000 (NT622) words | Day of tutorial | 60 |

| Presentation | About half of the session | Day of tutorial | 15 |

| Leading the seminar | About half of the session | Day of tutorial | 15 |

If no student is allocated the seminar topic for a particular week, the seminar will consist of a class discussion instead. The discussion will be lead by the lecturer or by a student conscripted for the purpose.

All students must read up on the seminar topic. This is particularly important for the weeks in which no tutorial is presented. Come prepared with something to contribute to the discussion. This might be a statement or question on one of the salient points of the topic. E.g. “After considering the issues, I have come to the conclusion that ‘blah’ is the best position to take on this issue.” My hope is that these seminars will develop your skills in doing theology in a group context.

This assignment consists of preparing the exegetical basis of a sermon or Bible study or youth group devotion. One of the passages given in the schedule, above, will be allocated to students doing this assignment. You may restrict your treatment to less than the whole passage, but not to less than ten verses. The submission should concentrate on the “exegetical skeleton rather than the expository flesh”, to quote Steve McAlpine. That is, focus on analysing and investigating the text, drawing out its meaning and seeking its true sense rather than the particular wording you would use to deliver these insights to an audience.

Note

The presentation may not be on the same passage of text as any other one of your written submissions covering exegesis.

An outline is required to be distributed one week prior to the presentation date. The student will give a short (about five minutes) presentation of the salient features during the corresponding exegesis session.

The written submission must include:

A short (about 50 words) description of your audience and the setting

Exegetical notes (about 1200 words) on: the relationship of the passage to the broader context; the main thrust and purpose of the passage; issues relating to textual variants, the cultural background of the people to whom the Epistle was addressed, and the historical setting; theological issues; a strategy for handling any contentious or hurtful issues that may be raised; applications of the text which are appropriate for your audience

a separate outline (about a page) for distribution to the audience.

Marks will be allocated as follows:

Table 10. Sermon or Bible study assessment

| Component | Extent | Due date | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outline | About one page | One week prior to presentation | 10 |

| Paper | 1500 words | Day of presentation | 80 |

| Presentation | About five minutes | Day of presentation | 10 |

The Greek translation assignment requires translation of three (NT432) or four (NT632) sections of text which the student may choose from the passages given in the schedule. Each section must be contiguous (i.e. no verses missed), at least ten verses long, and not from the same passage as any other chosen section.

Note

The translation may not be on the same passage of text as any other one of your written submissions covering exegesis.

Essential components include:

an interlinear, literal translation

a dynamic equivalent translation

notes on alternative readings (i.e. textual variants), alternative interpretations of words and passages (lexical and grammatical), Old Testament sources (e.g. if the text of a quotation follows the LXX rather than the MT, say so), and any other significant translation issues

a bibliography.

Note

All components must be your own work. Whether you include accents is up to you. The extent of accentuation advocated by J. W. Wenham (The Elements of New Testament Greek, vii-viii) is sufficient.

Marks will be allocated as follows:

Table 11. Translation assessment

| Component | Extent | Due date | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interlinear translation | 30 | ||

| Dynamic equivalent | 30 | ||

| Notes | 30 | ||

| Bibliography | 10 | ||

| Three (NT432) or four (NT632) sections of text for a total of 1500 (NT432) or 2000 (NT632) words | Thursday, 28 April 2005 |

The book review assignment consists of selecting a book from those listed below, reading it, and writing a critical review.

Croy, N. Clayton. Endurance in Suffering: Hebrews 12:1-13 in Its Rhetorical, Religious and Philosophical Context. SNTSMS 98. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Dunnill, J. Covenant and Sacrifice in the Letter to the Hebrews. SNTSMS 75. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Guthrie, G. H. The Structure of Hebrews: A Text-Linguistic Analysis. NovTSup 73. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1994.

Hughes, Graham R. Hebrews and Hermeneutics: The Epistle to the Hebrews as a New Testament Example of Biblical Interpretation. SNTSMS 36. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Hurst, L. D. The Epistle to the Hebrews: Its Background of Thought. SNTSMS 65. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Käsemann, Ernst. The Wandering People of God: An Investigation of the Letter to the Hebrews. Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1984. German original, 1939.

Kurianal, James. Jesus Our High Priest: Ps 110:4 as the Substructure of Heb 5:1-7:28. European University Studies Series 23, vol. 693. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2000.

Peterson, David. Hebrews and Perfection: An Examination of the Concept of Perfection in the 'Epistle to the Hebrews'. SNTSMS 47. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Note

The review may not be on the same topic as your tutorial paper (if doing NT622) or the same material covered in your exegesis paper.

A seminar will be held in week 6 to discuss issues raised to date through reading and class work. Students should have completed reading their chosen book by this time. Another seminar will be held in week 8 (immediately following the non-teaching break) for presentation and discussion of the reviews.

An outline of the review is required to be distributed at the seminar in week 6. The student will give a presentation and lead a discussion of the completed review at the seminar in week 8.

The review must follow the normal conventions and include all of the usual features. It should be “camera ready”; that is, formatted correctly as if ready to be printed in a journal. Examples can be found in journals such as New Testament Studies and Novum Testamentum.

Marks will be allocated as follows:

Table 12. Book review assessment

| Component | Extent | Due date | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outline | About one page | Thursday, 31 Mar 2005 | 10 |

| Review | 2000 words | Thursday, 28 April 2005 | 70 |

| Presentation | About five minutes | Day of presentation | 10 |

| Leading the seminar | About five minutes | Day of presentation | 10 |

This assignment consists of writing a full exegesis of a passage of text. For this purpose, each student will be allocated one of the passages given in the schedule, above.

Note

The exegesis paper may not be on the same passage of text as any other one of your written submissions covering exegesis.

Essential components include:

the main thrust and purpose of the passage

the relationship of the passage to the broader context

structural analysis, interpretation issues (lexical and grammatical) and textual variants

the historical setting, cultural background and thought world of the people to whom the Epistle was addressed

theological issues

approaches to dealing with any sensitive issues that may be raised by the text

the relevance of the text to the present.

The paper should cover all of these components adequately, and should not focus unduly on some aspects at the cost of others. For example, you should not devote more than a quarter of the paper to the “relevance” item.

Marks will be allocated as follows:

Table 13. Exegesis paper assessment

| Component | Extent | Due date | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exegesis paper | 3000 words | Thursday, 2 June 2005 | 100 |

Essay writing is an important skill to develop when studying theology. Here are a few pointers that you may find helpful. Writing can be broken down into the steps of discovery, analysis, integration and presentation.

The first part of coming to grips with a subject is the investigation stage -- the detective work. You have to use whatever resources that you have at your disposal to find out what you can about the subject. This means talking to people in the know, using logical deduction from first principles and reading learned works on the topic. For theology students, the latter is the usual place to start. You might also consider a web search; it's surprising what you can turn up provided that you have the critical skills to discern what is useful.

Computer programmers use acronyms like FIFO (first in, first out), LIFO (last in, first out), FILO (first in, last out) and GIGO (garbage in, garbage out). Taking their lead, we might coin these acronyms for the discovery phase:

- NINO

Nothing in, nothing out: If you don't do any ground work then the value of the content of your essay will be precisely zero. It may look nice and have your name in the right place, but it will be worthless.

- PINO

Plenty in, nothing out: There is no shortage of books on theology. As someone once said somewhere, “of many books there is no end, and too much study wearies the soul”. This is true; you can wear yourself out on the discovery phase and have no time or energy left for anything else. To avoid this unhappy end, allocate enough time and effort for discovery then move on.

- HIHO

Half in, half out: This is regurgitation of undigested text. You look for something that looks relevant, change its appearance a bit, then reproduce it. At worst, this is plagiarism. At best, it is a waste of time. You only gain something when you engage the text -- live with it, think about it, eat, drink and breathe it.

- GIGO

Garbage in, garbage out: This is self-explanatory: Not everything that you hear or read is true. Test everything and hold on to what is good.

Tole lege. Tole lege! Take up and read! Start with the abstract, introduction and conclusion to see whether it is relevant. If not, move on. Once you have selected a pile of relevant reading, sit down to feast. If you have trouble digesting the content, you might find it useful to read a paragraph at a time, taking notes at the end of each. Otherwise it's EIEIO -- in one ear and out the other.

Some might think of analysis as anathema to theology. Nevertheless, breaking things down into their elements is a good discipline. It is a process of distillation, whereby the essentials are extracted and the superfluities left behind.

The analysis phase isolates the key aspects of an issue. You will find that there are many works but few original ideas. Remember the catch cry of the Renaissance: Ad fontes! -- Go to the sources! Go to the first person to put forward a particular viewpoint if you can. There are times when you can't, as when the book is in some obscure tongue or isn't in the library. You will then have to settle for the interpretation of others -- “as through a looking glass, dimly”.

Now it is time to let your meal digest. What do I make of all these views? Imagine a room full of speakers, each about to present the views you have isolated. Then let the bun fight begin!

- Speaker A

I believe that the import of all this is “blah”.

- Speaker B

Surely you jest! You must not be aware of my work, The Zorgonness of Zang. It clearly demonstrates that “blah” is a proleptic epiphany.

- Speaker C

Ahem. I wrote Zang. I think that you might have misunderstood what “zang” means.

- Speaker B

Blush...

You get the idea. This is a demonstration of the dialectic approach. It involves stating a thesis (e.g. “flowers are pink”), then one or more antitheses (e.g. “roses are red, violets are blue”). Next comes synthesis, the most important step. Here, you try to construct a reasonable position that takes account of the strengths and weaknesses of the others (e.g. “roses are red, violets are blue; flowers are pink, and other hues too”.

Once you have given all substantive sides of the argument and constructed a reasonable synthesis, write a conclusion and introduction and you are done -- almost.

Conventions are important. Without them, your kettle would not plug into the power socket, your TV would not plug into your DVD, and every book would be arranged according to the author's whim.

There is a long tradition of book conventions that goes back well before the invention of printing. These conventions make life easier for the reader, who knows to expect a title page and table of contents at the beginning and an index at the end.

Style guides set out the conventions to follow in an essay. The BTC has produced A Guide to the Presentation of Essays, which tells you what you need to know. Turabian's Manual for Writers is good to have as well.

Apart from having worthwhile content in your essay, nothing is more important than the bibliography. It demonstrates that you have adequately investigated the topic and provides an important resource for others who may wish to discover more about the subject. A poorly composed bibliography is a sure sign of an amateur.

Bibliographies are a pedant's delight. They take a long time to get right and you can get caught out by leaving too little time for your bibliography. Do yourself a favour and record the bibliographical details of each work that you consult as you consult it. Get into the habit of being pedantic about this -- adopt a convention then stick to it, recording everything that the convention demands.

There is no point copying references from another bibliography -- only include what you have actually read. You don't need to read all of a book to include it in your bibliography -- just the relevant parts.

If you are wondering how many references is enough, here is a rough guide. For work at this level, you should aim for at least seven, including commentaries, monographs and journal articles. Recent and relevant journal articles are a very useful place to start because they are up to date and point you to the most important works in the field, assuming that the author has done his or her work properly. Use a finding aid such as the journal New Testament Abstracts to identify journal articles on your topic. The American Theological Library Association's religion indexes are helpful as well.

All students should have a copy of the BTC Guide to the Presentation of Essays, which incorporates ACT requirements.

Refer to the Student Handbook for the following:

assessment and academic progress, including learning outcomes

Bible versions

grievance and appeals procedures.

A copy of the current ACT Undergraduate Manual is in the BTC library, but may not be borrowed.

Table of Contents

- 1. History: How did we get Hebrews?

- 2. Canon: Should we accept Hebrews?

- 3. Circumstances: The author, audience, date and destination of Hebrews

- 4. Strategy: Why is Hebrews written like it is?

- 5. Sources: Where did the content come from?

- 6. Theology: What does Hebrews say about God?

- 7. Christology: What does Hebrews say about Christ?

- 8. Covenants and priests: What does Hebrews say about the Old and New Testaments and the role of human mediators?

Table of Contents

As Christians, we believe in a powerful God. “In the past, God spoke to us through the prophets, but in these last days has spoken to us by his Son.” It is wonderful to consider how our sacred texts have been preserved through the ages -- a process that certainly involved humans, but in which the eyes of faith can discern divine agency as well. We do not claim that our texts are word perfect copies of the originals; rather, we say that our scriptures bear true witness to the One of whom they speak.

It is clear that in order for us to get Hebrews, someone had to write it. In another lecture we will look more closely at the question of the writer's identity. Today, we will look at the process by which Hebrews was handed down to us.

Before the invention of mechanized printing, written works had to be reproduced by hand. A hand copy is called a manuscript, often abbreviated as MS, with MSS used for the plural. There were costs associated with making a copy -- writing materials and the scribe's hire, unless you made your own copy. Consequently, only those writings considered to be worthy were consistently copied. This tended to make the survival of a particular writing dependent on its popularity.

Certain fundamental aspects of the process through which the Greek New Testament arrived in our hands are unknown: How many copies were made? How many have survived? How many generations of manuscripts stand between the original compositions (i.e., the autographs) and the surviving MSS which form the basis of today's Greek text?

Other aspects are better known: What were the MSS like? Is the text we have the same as the original? If variations occurred, how did they happen? If there are variations, how do we restore the original?

The population of the Roman Empire was about fifty million during the first three centuries CE. The Christian community began small. According to Acts there were about five thousand individuals after Pentecost, around 33 CE. By 300 CE, the Christian population was much larger, despite various attempts at suppression (e.g. the great persecution (303-312) and the persecutions of Decius (250-251) and Valerian (257-260)). No one knows what proportion of the Empire's population was Christian by the time that Galerius issued the edict of toleration (311). The burgeoning Christian population may well have been what provoked the politicians to firstly instigate the persecutions and finally to adopt a conciliatory approach once they realised that resistance was useless.

A sociologist or political scientist might know at what point a formerly illegal movement becomes officially tolerated through its adherents' force of numbers; to some extent the answer depends on whether the movement is peaceful or violent. If we guess conservatively at a proportion of about one tenth of the entire population, then there would have been about five million Christians in the Empire when Galerius decided he had better make his peace with them.

Christians prized their scriptures, and no self-respecting church would be without its own copy of the Gospels, a copy of Paul's letters, the Apostolos (i.e. Acts plus the Catholic letters), and a few other books as well. The word "book" is used advisedly -- if Christians were not the inventors of the codex, they were certainly the first to use it on a large scale. It allowed a whole collection of writings to be contained in a single, portable unit that was far superior to the roll when it came to finding a particular place in the text.

Given that every church would like to have its own copy of Paul's letters, we can make a rough estimate of how many copies existed at any one time in this early phase of Christian history. Using the logistic growth equation, a growth rate of five percent per annum, and applying bounds of five thousand individuals in 33 CE and five million in 300 CE, the Christian population would have increased as shown here:

The number of MSS can be estimated if we know the size of the Christian population, the average number of members per church and the average number of MSS per church. Assuming that every church had, on average, one copy of Paul's letters and one hundred members, the number of MSS in use at various times would be roughly as given here:

Note

This assumes that the first copy of Paul's letters appeared in 100 CE and that every church had a copy by 150 CE. The number of churches implied by these figures may seem very large. (Apart from 100 CE, there is a one to one correspondence between churches and MSS.) There may not have been fifty thousand church buildings in 300 CE, but there may well have been that many house churches in operation. These figures neglect to account for personally owned MSS.

There are approximately five thousand Greek MSS and more in such languages as Latin, Coptic and Syriac. Most are late copies, with only a few hundred Greek MSS dating from the first millenium. If the estimate above is roughly correct then only a very small proportion of the earliest copies has survived.

A great deal of information concerning the surviving MSS is found in Nestle-Aland's Novum Testamentum Graece (1993, appendix 1). This shows that approximately thirty copies of Hebrews, in various states of repair, survive from the first millenium. In general, these early copies are the most valuable when it comes to determining the ancient text.

It is very important to know how many generations of MSS intervene between the original, also called the autograph, and our earliest MSS. It is hard to say what the answer might be, and almost no one has tried. I wrote a copying simulation program in an attempt to gain some insight into the question. Whether or not it goes anywhere near reflecting the realities of the actual process remains a big question. There are all kinds of variables involved. If I were to hazard a guess, I would say that there is a good chance that some of our surviving MSS are within five generations of their respective originals. Unfortunately, we can't tell which ones they are.

It is easy to tell what the MSS were like because we have survivors. Some are extremely ancient. For example, P52 is dated to the first half of the second century.

Two major forms existed: the roll and the codex. The roll placed an upper limit on the size of a written discourse. Some think that Luke and Acts had to be published separately because of this practical limit. Happily, the barrier fell once Christians adopted the codex.

The capacity of codices seems to have grown gradually. At first, a single gospel might fill a codex. Shortly afterwards, collections began to be bound together -- perhaps two gospels or Paul's letters would fill a typical codex at the end of the first century CE. For Irenaeus (c. 180 CE), it was as natural to have four gospels as it was to have four winds. By the time Athanasius wrote down his New Testament canon (367 CE), there were codices that contained the entire New Testament. Interestingly, the progression of codex capacity as outlined here is roughly linear with time.

Table 1.2. Codex capacity vs date

| Date (CE) | Contents | Capacity (pages) |

|---|---|---|

| 70 | one gospel (Matt) | 50 pages |

| 100 | two gospels (Matt and Luke) or Paul's letters | 120 pages |

| 180 | four gospels | 180 pages |

| 367 | entire canon | 400 pages |

Note

For the purpose of this exercise, the entire New Testament is taken to contain 100,000 words, and codex pages are assumed to contain 250 words. The actual capacity of a codex page was variable as codices had no fixed format.

No one knows what made the early Christians adopt the codex. Perhaps Mark thought he would try using a codex for his gospel? That might explain the abrupt ending: the last page of the original could have been torn off! Whatever the reason for its adoption, the codex provided a means of binding together collections of related writings. One of the first collections of this kind was Paul's letters.

Some think that Paul's writings were circulating as a collection by the end of the first century. There is a direct reference to such a collection in the account of the martyrs of Scilli (Stevenson, 1987, 44) in 180 CE. We don't know who gathered Paul's letters or how. Perhaps it was an individual -- Luke, Mark or another one of Paul's companions. Then again, a number of churches may have compiled their own collections. In Col 4.16, Paul himself encourages such a practice.

Whether Hebrews was included in this collection (or these collections) is yet another unknown. Its inclusion in a very early version of Paul's letters would help to account for the survival of this unique writing. Whatever happened, the earliest Greek MS of Paul's letters includes Hebrews. The MS is designated P46, and is dated c. 200 CE. You can see an image of one page of this codex here.

Yes and no. For my PhD dissertation, I transcribed the text of the papyrus and uncial MSS of Hebrews, which range in date from c. 200 CE to the tenth century. It was wonderful to hold P13 in my hands -- a roll that is about 1700 years old. After completing the transcriptions, I wrote collation programs that listed every difference. Hebrews has about five thousand words, and it turns out that variations occur in about two thousand. In effect, virtually every word that can vary, does vary. There is not much that a scribe can do to simple words like "and", "the" and "but". However, more complex words are prone to every manner of alteration.

That said, the very great majority of variations are insignificant. Dictionaries did not exist, so scribes spelled as they were taught. Spelling and other orthographical differences account for many of the variations. Most lexical variations -- those where the words actually differ -- are of minor significance. Apart from changes of word order, there might be a missing article here and added conjunction there; nothing earth shattering. There are, however, some interesting variants -- ones that have a significant effect on the meaning. A good example is found in Heb 2.9.

As a consequence of textual variation, we cannot be certain what the original text was. It is very likely that in all but a few cases the original text is preserved among the variations. The problem then becomes one of trying to discern the original text at each point of variation.

Variants occurred as copies were made for no other reason than the human fallibility of the scribes. I suppose that God could have preserved the exact text of the originals by taking control of every copyist. However the manifest fact is that he did not. It is actually quite difficult to make a copy of any sizable text without introducing errors. In fact, the presence of variants in the New Testament manuscript tradition is a sure sign of its authenticity.

When a copy was commissioned, the scribe would take an exemplar and a blank codex or roll then sit down and copy away. Sometimes he or she would make transcription errors. Users of the resultant MS would correct these errors as they thought best. In some cases, this process resulted in the reading of the exemplar being restored. In other cases, it resulted in the reading of another MS being inserted, as when a dilligent corrector consulted another MS to see what the text should be. In yet other cases, it resulted in the creation of novel readings.

When the texts of the MSS of Hebrews are compared, it is apparent that some have similar texts. They are never identical, but they can be very close. It is possible to produce a "map" of MSS where similar texts are located closer to each other than dissimilar ones.

Similarity can be due to common ancestry but can also be caused by common locality. There was no reason why a MS could not be imported from another region of the Empire, but the easiest way would be to get an exemplar from nearby. It follows that MSS from a particular region would tend to be similar because they were likely to be copied from and corrected against the same exemplars. If textual and spelling variations are mapped, the distribution of MSS in the textual map tends to recur in the spelling map. Other things being equal, this fact can be interpreted to mean that MSS with similar texts have a shared ancestral home.

Note

These maps show the first two axes extracted through multivariate analysis of (1) textual and (2) spelling variations found among the MSS shown. The textual map is based on 401 units of variation while the spelling map is based on 200 units.

With the exception of a few words here and there, the original text (but not the original spelling) is likely to be preserved somewhere among the MSS. Recovery of the original text is then a matter of going through the places where variation occurs and attempting to discern the original reading at each one. This is done by applying various tests:

prefer the earlier reading

prefer the more difficult reading

prefer the reading which recurs in diverse witnesses.

One of the correctors of Codex Vaticanus knew the first of these. Another scribe had crossed out an ancient reading at Heb 1.3 and substituted the more common one. The corrector then reinstated the old reading, and added in the margin "Bad and ignorant scribe; leave the old reading alone!"

These are not the only tests, and none is a sure guide. In the end, it may be best to stick with the text of an early MS that seems to have consistently primitive readings. Codex Vaticanus was regarded by Westcott and Hort as the best MS. The United Bible Societies' Greek New Testament text is quite close to that of Codex Vaticanus. Unfortunately, the last part of Hebrews is missing from this codex, so we must turn to other MSS such as P46 or Codex Sinaiticus to fill in the gaps. Where it is difficult to discern which reading is original, we can do no more than ackowledge that any of the alternatives may be what the author wrote, and accept that only God knows.

Table of Contents

The word “canon” means rule. In relation to the New Testament, it is the rule that states which writings are to be accepted as scripture and which are not. Souter (1954, 143) gives this definition:

A κανών is a list of biblical books which may be read in the public services of a church, and, if such be produced with the authority of a synod or council, of the Church.

The first use of the word in this sense is in Athanasius' Decrees of the Synod of Nicaea (c. 350 CE), when he describes the Shepherd of Hermas as not belonging to the canon.

Before the concept of a list of approved books emerged, canonicity was more a matter of the authority that leading lights ascribed to a book. Some of the New Testament books had it easy -- their authority was never questioned. Hebrews, on the other hand, struggled for acceptance.

These rules can be applied to decide what should be in and what should be out. What rules would you come up with?

- Obeys the “rule of faith”

Conforms to the fundamental truths of Christianity.

- Apostolic

Derives from an apostle (e.g. Matthew, John) or an associate (e.g. Mark, Luke).

- Acceptance by the Church

“A book that had enjoyed acceptance by many churches over a long period of time was in a stronger position than one accepted by only a few churches, and then only recently.” (Metzger 1987, 253)

One might add to this “opinions of influential figures”.

Why isn't inspiration a criterion? Metzger (1987, 254-7) gives an explanation.

Hebrews has been quoted since the earliest days of the church. Clement of Rome makes use of Hebrews in 1 Clement (c. 95 CE). Polycarp (early 100s) almost certainly knew Hebrews. Whoever wrote the Shepherd of Hermas (c. 120-140) seems to have known Hebrews (Lane 1991, clii), and the unknown author of 2 Clement (c. 150) may have known Hebrews too. Marcion (c. 145) may have known Hebrews, but, not surprisingly, did not include it in his Apostolicon. Justin Martyr (c. 150) knew and Hebrews and used it.

Pantaenus (c. 180) was the first head of the catechetical school at Alexandria. According to Eusebius (Hist. eccl. vi. xiv. 4), Pantaenus ascribed Hebrews to Paul, who wished to remain anonymous in this instance:

Since the Lord, being the apostle of the Almighty, was sent to the Hebrews, Paul, having been sent to the gentiles, through modesty did not inscribe himself as an apostle of the Hebrews, both because of respect for the Lord and because he wrote to the Hebrews also out of his abundance, being a preacher and apostle for the gentiles. (Metzger 1987, 130)

Clement of Alexandria (c. 190), a learned man, followed Pantaenus as head of the catechetical school. He accepted Pantaenus' view on Hebrews, adding that it might have been translated into Greek translator by Luke.

Origen (c. 185-254), a real prodigy, succeded Clement when still young. He quoted Hebrews more than two hundred times, but had doubts whether it was Paul's own work:

He gives as his considered opinion that, in view of the literary and stylistic problems involved, it is best to conclude that, though the Epistle contains the thoughts of Paul, it was written by someone else, perhaps Luke of Clement of Rome. (Metzger 1987, 138)

Eusebius (c. 260-340) sought a canon. The best he could do was to list books that were generally received, those that were generally rejected, and those that were accepted by some and rejected by others. He included Paul's letters, and, by implication, Hebrews, in the first category. He noted that Hebrews was “disputed by the church of Rome, on the ground that it was not written by Paul”. (Metzger 1987, 203)

We have two great uncials from this era -- codices Vaticanus and Sinaiticus. Both have Hebrews, although the last part of the ancient text is missing in Vaticanus.

Cyril of Jerusalem (c. 315-86) included the fourteen Epistles of Paul in his list, which means that he accepted Hebrews.

Athanasius (c. 296-373), as bishop of Alexandria, wrote a Festal Letter to the Egyptian churches every year setting down the dates of Easter and other Christian festivals. In 367 he included a canon list comprised of the same 27 books of the New Testament as used today.

The Western Church accepted the possibility of post-baptismal repentance, in line with the Shepherd of Hermas. This doctrinal stance may account for the Western Church's reluctance to accept Hebrews as authoritative.

Irenaeus (c. 180), the presbyter Gaius (c. 200), and Hippolytus of Rome (c. 170-235) knew and used Hebrews but did not regard it as apostolic. The Muratonian Canon, from about the same time, does not include Hebrews among the list of documents regarded authoritative in the church of Rome.

Tertullian from Carthage in Africa, became a Christian in Rome around 195. After returning to Africa, he joined the Montanists. Tertullian wrote in Latin. He spoke of the "rule of faith", the Christian fundamentals transmitted by the baptismal formula now known as the Apostles' Creed. Tertullian cites Hebrews, which he thought was written by Barnabas, “a man sufficiently accredited by God as being one whom Paul had stationed next to himself”. (Metzger 1987, 159)

Cyprian (c. 200-258), also of Carthage, was converted about 246 at which point he gave away his wealth and became an ascetic. Only two years later, by popular choice, he was made bishop of Carthage, and there remained until martyred. Cyprian quoted extensively from the New Testament, but not from Hebrews. He was perhaps influenced by numbers, seeing correspondence between the four rivers of Eden and the four Gospels, the seven churches and the seven letters of Paul. Hebrews would have made eight. This kind of logic was popular at the time.

Cyprian's apparent omission of Hebrews from the canon represents a low point in its fortunes in the West. Soon afterwards, Hilary (d. 368) ascribes Hebrews to Paul and treats it as scripture. Hilary defended the orthodox line against Arianism at the Council of Seleucia (359); the exalted view of the Son painted by the author of Hebrews provided powerful ammunition in this fight.

Others in the West such as Lucifer of Cagliari (d. 370), Philaster (d. 397), and Rufinus (b. 345) accepted Hebrews.

This brings us to the time of Jerome (346-420), editor of the Vulgate. In 414 he wrote (Epist. cxxix):

The Epistle which is inscribed to the Hebrews is received not only by the Churches of the East, but also by all Church writers of the Greek language before our days, as of Paul the apostle, though many think that it is from Barnabas or Clement. And it makes no difference whose it is, since it is from a churchman, and is celebrated in the daily readings of the Churches. And if the usage of the Latins does not receive it among the canonical Scriptures, neither indeed by the same liberty do the Churches of the Greeks receive the Revelation of John. And yet we receive both, in that we follow by no means the habit of today, but the authority of the ancient writers, who for the most part quote each of them, not as they are sometimes to do the apocrypha, and even also as they rarely use the examples of secular books, but as canonical and churchly. (Metzger 1987, 236)

Augustine (354-430) at first thought that Hebrews was by Paul. Later he varied between it being by Paul or someone unknown. Finally, he always referred to it as anonymous. If uncertain about its authorship, he had no doubts about its authority, and included Hebrews in his canon (Metzger 1987, 237). Synods at Hippo (393) and Carthage (397 and 419) endorsed Augustine's list of twenty seven, including Hebrews.

Westcott (1899, lxvi) summarized the early situation:

At Alexandria the Greek Epistle was held to be not directly but mediately St Paul's, as either a free translation of his words or a reproduction of his thoughts. In North Africa it was known to some extent as the work of Barnabas and acknowledged as a secondary authority. At Rome and in Western Europe it was not included in the collection of the Epistles of St Paul and had no apostolic weight.

After the fifth century, Hebrews enjoyed rest from its struggles for a long time. There was a brief review of its status during the reformation; Luther and others relegated Hebrews along with some other books to a secondary rank within the canon, but did not exclude it.

What made the church accept Hebrews but not, say, the Epistle of Barnabas?

Instead of suggesting that certain books were accidentally included and others were accidentally excluded from the New Testament canon ... it is more accurate to say that certain books excluded themselves from the canon. Among the dozen or more gospels that circulated in the early Church, the question how, and when, and why our four Gospels came to be selected for their supreme position may seem to be a mystery--but it is a clear case of survival of the fittest. As Arthur Darby Nock used to say to his students at Harvard with reference to the canon, “The most travelled roads in Europe are the best roads; that is why they are so heavily travelled.” William Barclay put the matter still more pointedly: “It is the simple truth to say that the New Testament books became canonical because no one could stop them doing so.” (Metzger 1987, 286)

And so it is with Hebrews.

Table of Contents

Although Hebrews concludes like other New Testament letters, it does not begin like one. As a result, we do not have the author's name.

The letter itself tells us that the author:

seems to be Jewish, having an intimate knowledge of Jewish history and customs

is a Christian who “had the message of salvation demonstrated by those who heard the Lord ” (Heb 2.3)

seems to be a Greek-speaking Christian who is familiar with the message preached by Stephen (cf. Acts 6-7)

knows Timothy, an associate of Paul (Heb 13.23)

is with some Italian Christians (Heb 13.24)

seems to be male. Heb 11.32 says, “And what else can I say? There is not enough time for me to keep going on about Gideon, Barak, Samson, Jephthae, both David and Samuel, and the prophets.” The word here translated as “to keep going on” is διηγούμενον, a first person, masculine, singular participle.

has a large vocabulary. Hebrews has 4942 words, and uses 1038 different words. Of those, 169 are unique to Hebrews when compared with the New Testament. [Lane 1991, l]

is eloquent, trained in rhetoric

may be familiar with Alexandrian Jewish theology

is familiar with the LXX (i.e. the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible). For example, Heb 10.5 quotes Ps 40.7 (LXX), which reads “you did not desire sacrifice and offering, but you prepared a body for me.” However, the Hebrew Ps 40.6 (MT) reads “you did not desire sacrifice and offering, but you made me willing to listen and obey.”

composed in Greek and did not translate the letter from Hebrew. The first goes without saying; the second is implied because the argument relies on subtleties of the Greek languange: Heb 9.15-20 makes use of the dual sense of διαθήκη, meaning both “covenant” and “testament”. The corresponding Hebrew word berit does not have the same double meaning.

All kinds of people have been suggested as author. The list below gives the most popular alternatives, with our source of each suggestion in parentheses:

- Paul (Eastern Church, second century)

For: At least in the Eastern Church, the letter is included in early collections of Paul's letters, which probably date back to the early second century. Clement of Alexandria (c. 190), followed Pantaenus in saying that Hebrews was by Paul, but added that it was translated from Hebrew to Greek by Luke, who then published it.

Against: Heb 2.3 does not fit well with Paul. Furthermore, the style is not Paul's. Origen, in the first half of the third century, said this:

The character of the diction of the epistle superscribed To the Hebrews lacks the apostle's rudeness of expression (a rudeness of expression which he himself acknowledged); the epistle is more idiomatically Greek in the composition of its diction. This will be acknowledged by anyone who is skilled to discern differences of style. But on the other hand the thoughts of the epistle are admirable and in no way inferior to those of the acknowledged writings of the apostle. The truth of this will be admitted by any one who pays attention to the reading of the apostle...

For my own part, if I may state my opinion, I should say that the thoughts are the apostle's, but that the style and composition are the work of someone who called to mind the apostle's teaching and wrote short notes, as it were, on what his master said. If any church, then, regards this epistle as Paul's, let it be commended on this score; for it was not for nothing that the men of old handed it down to us as Paul's. But as to who actually wrote the epistle, God knows the truth of the matter. According to the account which has reached us, some say that the epistle was written by Clement, who became bishop of the Romans; others, that it was written by Luke, the writer of the Gospel and the Acts. [Bruce 1990, 15, quoting Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. 6.25.11-14.]

- Clement of Rome (Origen, third century)

For: An Alexandrian tradition, given to us by Origen.

Against: If Clement wrote Hebrews, he “turns his back on its central argument in order to buttress his own arguments about the Church's Ministry by an appeal to the ceremonial laws of the Old Testament.” [Bruce 1990, 14, quoting T. W. Manson, The Church's Ministry (London, 1948).] Also, “It cannot be assigned to Clement, because Clement ... has too pedestrian a style to have been capable of creating that masterpiece.” [Manson 1951, 170]

- Luke (Origen, third century)

For: An Alexandrian tradition, given to us by Origen.

Against: “Luke belonged to Gentile, not to Jewish Christianity.” [Manson 1951, 170]

- Barnabas (Tertullian, third century)

For: A tradition given to us by Tertullian, possibly received from Asia Minor. Barnabas is called “son of exhortation” in Acts 4.36. Hebrews styles itself as “words of exhortation” at 13.22.

Against: Had Clement of Rome known that Barnabas wrote Hebrews, surely he would have said so. However, knowledge of the author may already have been lost.

- Timothy (certain manuscripts)

For: Minuscules 1739, 1881 and many Byzantine manuscripts have the subscription, “written from Italy by means of Timothy.”

Against: These are generally late MSS. Heb 13.23 seems to be against Timothy being the author.

- Apollos (Martin Luther, sixteenth century)

For: Acts 18.24 describes Apollos as a Jew, born in Alexandria, an eloquent speaker, mighty in the Scriptures. This certainly fits the author of Hebrews.

Against: There is no early tradition that Apollos wrote Hebrews. Surely the Alexandrians would have recounted such a tradition if it existed in their time. Surely, if Clement of Rome knew Apollos wrote Hebrews, he would have mentioned the fact when writing 1 Clement to the Corinthians, seeing that Apollos had visited Corinth (Acts 19.1).

- Priscilla and Aquila (Adolf Harnack, 1900)

For: They were teachers; they are associated with Timothy; they hosted a house church in Rome (Rom 16.3-5); the use of both “I” and “we” in Hebrews is explained by dual authorship; a female author may explain how authorship details were lost so early -- the early church may have suppressed the information (cf. the apparent bias against Priscilla displayed by Codex Bezae, a fifth century representative of the Western text).

Against: There is no early tradition that Priscilla and Aquila wrote Hebrews.

- someone else (various)

Among other suggestions are Silas, Epaphras, Philip, Stephen, Jude, and Mary, the mother of Jesus.

In the end, the best answer is Origen's: “God knows.” It may well have been someone who is not even mentioned here.

[Bruce 1990, 14-20] [Manson 1951, 167-172] [Moore 1994, 332-3]

Lacking any reliable early tradition, we turn to the letter for clues about the people to whom it was addressed. We can create a profile by reading between the lines. Accordingly, the audience may be characterised as:

- known to the author

The author is familiar with the audience's past and present circumstances. Timothy is their brother (Heb 13.23).

- Greek-speaking and Jewish

The author's constant use of the Septuagint in this “word of exhortation” shows that the audience regarded the Greek version of the Hebrew Bible as authoritative. This is not likely to have been the case if they were Hebrew-speaking or formerly pagan.

- second-generation Christian

This is implied by Heb 2.3, if indeed the author's “us” includes the audience.

- having witnessed God's power

Heb 2.4 and 6.4-5 indicate that the hearers had tasted the powers of the coming age.

- having suffered persecution

Heb 10.32-34 outlines privations the audience had already suffered for their beliefs.

- in danger of apostasy

The whole thrust of the letter is to convince the audience not to drift away, not to neglect the great salvation first announced by the Lord, not to turn from the living God, not to recrucify the Son of God, not to treat the Spirit of grace with contempt, not to draw back, not to refuse the One who speaks from heaven.

[Bruce 1990, 3-9] [Lane 1991, liii-lviii] [Moore 1994, 331-2]

Clement of Rome apparently referred to Hebrews when composing 1 Clement, which is dated about 96 AD. Also, Heb 2.3 (“which at the first having been spoken through the Lord, was confirmed to us by those who heard”) indicates that the author was a second-generation Christian. These give a terminus ante quem (literally “limit before which [it was written]”, meaning “latest possible date”) of about 95 AD.

In searching for a terminus post quem (i.e. “earliest possible date”), if the audience was in Rome then Heb 12.4 (“you have not yet resisted to the point of shedding blood”) would indicate that the letter was written before Nero attacked the Roman Christians in 65.

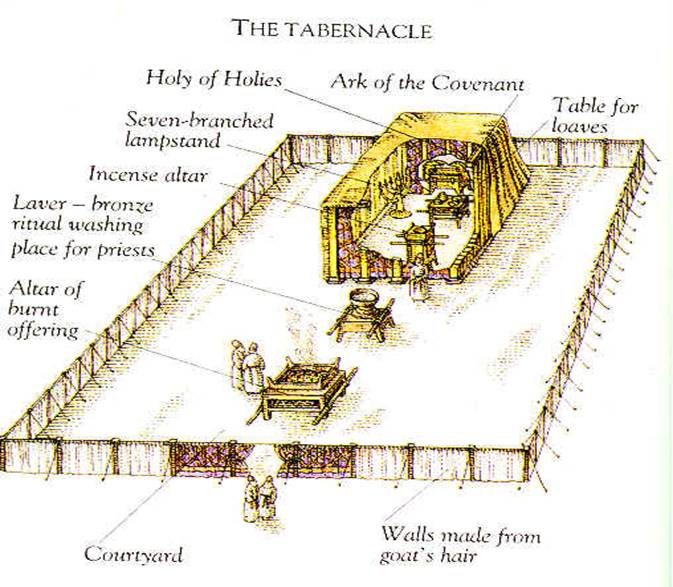

Lack of any mention of the demise of the temple would seem to indicate a date before 70. However, Hebrews does not mention the temple; rather, it refers to the tabernacle. It is therefore conceivable that the author wrote after the destruction of the temple but did not mention it. However, the repeated use of the present tense in Heb 9.6-9, which relates to the work of the Levite priests, indicates otherwise. Also, Heb 8.13 says, in reference to the Old Covenant and its priesthood, “that which is becoming old and grows aged is near to vanishing away.” These words would be particularly appropriate if the author wrote between 66, when the Jewish uprising against Rome began, and 70, when the temple was destroyed.

Heb 10.1-2 says, “For the law, having a shadow of the good to come, not the very image of the things, can never with the same sacrifices year by year, which they offer continually, make perfect those who draw near. Or else wouldn't they have ceased to be offered, because the worshippers, having been once cleansed, would have had no more consciousness of sins?” This would be somewhat out of place if the author knew the sacrifices had actually ceased.

Finally, the quotation of Ps 95 at Heb 3.7-11, with its mention of the forty years of testing, may be another indication that the author is writing just before 70 AD -- almost forty years after the death and resurrection of Jesus.

All things considered, a date just before 65 AD seems reasonable enough for the composition of Hebrews. This is only tentative -- any date between 60 and 100 AD is consistent with the evidence we have.

[Bruce 1990, 20-22] [Moore 1994, 332-3]

Just about every imaginable destination has been suggested, from Judaea to Spain:

- Jerusalem

So Sir William Ramsay, C. H. Turner and Franz Overbeck. However, Hebrews makes no explicit reference to the temple. Why should this be so, given the temple's prominence? Cf. Stephen's speech, which was delivered in Jerusalem and does mention the temple.

- Alexandria

For: The author seems to be familiar with Alexandrian literature such as Wisdom, 4 Maccabees and Philo.

Against: If the letter was sent to a chuch in Alexandria, why didn't Clement of Alexandria know only one hundred years later?

- Rome

Heb 13.24 says, "Those from Italy greet you." This would make sense if the author had some Italian companions and was writing to a church in Italy. However, it would also make sense if the author was writing from Italy to a church elsewhere. The only other use of the phrase “from Italy” in the New Testament is Acts 18.2, which says that Aquila and Priscilla had come from Italy after Emperor Claudius ordered Jews out of Rome.

Other points in support include:

The earliest extant literature that refers to Hebrews is 1 Clement, which was itself composed in Rome.

References to the audience's generosity and persecution in Heb 6.10-11 and 10.33-34 are consistent with what is known of the Roman church from other sources such as Ignatius and Eusebius.

The description in Heb 10.33-34 matches the circumstances of Claudius' edict of expulsion (49 AD).

The Greek word for leaders (ἡγούμενοι) used at Heb 13.7, 13.17 and 13.24 is also used in early literature referring to the church in Rome.

There are some notable supporters of a Roman destination, including J. J. Wettstein (the first to suggest it), Adolf Harnack and William Manson.

- Somewhere else

E.g. Samaria (J. W. Bowman), Syrian Antioch or Caesarea (C. Spicq), Colossae (T. W. Manson), Ephesus (W. F. Howard), Cyprus (Antony Snell), Corinth (H. Appel, M. W. Montefiore).

Even though Rome seems plausible, there is no certainty concerning the destination of Hebrews.

[Bruce 1990, 10-14] [Lane 1991, lviii]

Table of Contents

Hebrews has long been regarded as a letter -- a natural conclusion given that it has always circulated with Paul's letters. In our Bibles, it occurs at the end of Paul's letters. In P46, it comes after Romans. (Whoever copied P46 arranged the letters in order of length.) Later codices (Sinaitics A B C H I K P) place it after the letter addressed to churches but before those addressed to individuals (i.e. between 2 Thess and 1 Tim). That makes sense, doesn't it?

Hebrews ends like a letter but does not begin like one. (Neither does 1 John.) Instead, it begins like a sermon. Heb 13.22 says, “Brothers, I urge you to pay close attention to this word of exhortation, for I only wrote briefly.” Even though the author has written the letter or sermon, he regards it as a spoken piece: “about which we are speaking” (2.5), “the things that will be spoken about later” (3.5), “even though we speak this way” (6.9).

The phrase "word of exhortation" is used to preface the message given by Paul at Antioch in Pisidia (Acts 13.15-13.41). Do the two match? There are common elements: formal introduction, authoritative examples (typically scriptural quotations), conclusions taken from the examples and applied to the audience, and a final exhortation. In Hebrews, this structure recurs.

Whoever wrote Hebrews was a creative genius. It is clear that he had command of the spoken medium, and could convert something meant to be spoken into the written medium for the purpose of easy transport. Whatever its genre, a remarkable thing about Hebrews is the way the author makes it sound as if he is present, delivering the speech. He doesn't say “about which we are writing” but “about which we are speaking.” The audience members are treated as hearers, not readers.

The art of rhetoric is the art of persuasion. Those who listen carefully are well-acquainted with the force of the author's persuasive powers. Hebrews is a rhetorical tour de force. As an exercise, look up A Handbook of Rhetorical Devices and see how many of the rhetorical devices mentioned there are used in Hebrews.

Rhetoric was originally developed to help people win legal disputes, but soon became popular for political purposes. It is the art of making people act the way you want. This, in many cases, is ethically questionable. None however can question the motives of the author of Hebrews.

Aristotle identified three major genres for public speeches: deliberative, epideictic, and forensic. “Each genre is defined by the role of the audience, the subject matter, the ends, and the time.” [Smith, n.d.] These three may be defined as follows:

Deliberative rhetoric is speech-making directed at the future...; its business is exhortation and dissuasion, and its exemplary genre is the political speech. Forensic rhetoric is speech-making trained on the past; its business is accusation and defense, and its exemplary genre is the advocate's summation in a court of law. Epideictic rhetoric is the rhetoric of the present; its business, Aristotle says, is praise and blame, and its exemplary genre is the funeral oration. Epideictic rhetoric is, at the same time, a rhetoric of values: we praise people for embodying the values we admire and blame them for embodying the values we deplore. [Segal, n.d.]

Which types are used in Hebrews?

The world in which the author of Hebrews lived did not have TV. The people there were just as interested in what was going on, but had to get their news a different way. Back then, the medium was the spoken word. Audiences developed the art of listening and orators developed the art of speaking. If a speaker was no good at it then no one would listen.

Orators would include cues to alert the audience to the structure of what they were saying. They did not say, “full stop”, “new paragraph” etc. Instead, they used a range of techniques to let the audience know how what was being said was meant to hang together. Hebrews is rich in these features.

There have been many attempts to discover the structure of Hebrews. Many succeed in part, but none completely. Thien (1902) noticed that the author announces themes then develops them in reverse order. For example, Heb 2.17 has “our merciful and faithful high priest.” The “faithful” theme is developed first (3.1-4.13), followed by the “merciful” theme (4.14-5.10). Other examples are 5.9-5.10: author of eternal salvation (8.1-10.18) and a priest like Melchizedek (7.1-7.28), and 10.36-10.39: endurance (12.1-12.29) and faith (11.1-11.40).

Buchsel (1928) observed the alternation between exposition and exhortation -- the pattern according to which I have divided up the text for this lecture series.

Vaganay identified “hook words”: a rhetorical device used to tie together adjacent units of discourse; a word occurs near the end of one section and at the beginning of the next.

Descamps (1954) wrote about “characteristic terms” used within thematic units. For example, “angels” occurs 11 times in Heb 1.5-2.16 but only twice thereafter.

Albert Vanhoye (1963) building on the work of the others, listed an array of literary devices:

announcement of subject

transitional hook words

change of genre

characteristic terms

inclusio

symmetrical structures.

More recently, Guthrie (1991) has used discourse analysis, an approach based on the science of linguistics. He identified no less than nine ways that the author of Hebrews uses to move from one section to another including: “hook words”, “distant hook words”, “hooked key words”, “overlapping constituents”, “parallel introductions”, “direct intermediary transition” and “woven intermediary transition”.

After all this work, there is no consensus concerning the structure of Hebrews. We can see the author using an impressive range of techniques. But as with authorship and audience, we have to say with respect to the pattern that the author had in his mind, “God knows.”

Table of Contents

Hebrews is filled with quotations from the Greek version of the Old Testament scriptures, that is, the Septuagint (LXX). The author assumes the audience knows its scriptures well. The author treats scripture as the speech of God. He uses it as a source of archetypes for the fulfillment seen in Christ.

OT quotations may be the essential clue to the arrangement of Hebrews. This is not a new theory -- in the 1700s, Bengel recognized the importance of Psalms 2, 8 and 110 in understanding why Hebrews procedes as it does. More recently, Caird and others have come up with a set of OT quotations that they regard as the backbone of Hebrews: Ps 8 (Heb 2.5-2.18), Ps 95 (Heb 3.1-4.13), Ps 110 (Heb 4.14-7.28), Jer 31 (Heb 8.1-10.31), Hab 2 (Heb 10.32-12.2), Prov 3 (Heb 12.3-13.19). [Lane 1991, cxiv]

The author of Hebrews thinks like other New Testament writers. He has an apocalyptic outlook and looks forward to the end of the old order of things. The speech by Stephen in Acts has many points of contact. Parallels may exist with other New Testament writings as well (e.g. Heb 6 and 1 Cor 3). The idea of the priesthood of Christ is uniquely developed in Hebrews. However, it shows up in other places, even Revelation!

There is some evidence of reliance on an oral midrash on the Pentateuch (cf. 7.5, 7.27, 9.4, 9.19, 9.21, 12.21). [Bruce 1990, 27]

Fifty years ago, C. Spicq made everyone think that the author of Hebrews was influenced by Philo, an Alexandrian Jewish philosopher. More recently, others such as L. D. Hurst have pointed out that the apparent similarities between Hebrews and Philo could be due to common reliance on other forms of Judaism. According to Lane [1991, cviii]:

Hurst concludes that Philo and the writer of Hebrews shared a common conceptual background rooted in the Old Greek version of the Bible. Philo chose to develop certain OT themes Platonically. The writer of Hebrews, under the influences of Jewish apocalyptic and primitive Christian tradition, chose to develop them eschatologically.

When the Dead Sea Scrolls came to light, some people got the idea that Hebrews could now be understood as being addressed to a group from Qumran. Reasons in support include common points such as a Messiah-priest and fascination with Melchizedek. However, this theory is not so popular now. Reasons against include the context (Hebrews is hellenistic while the DSS material is semitic) and differences in the respective OT texts.

Kasemann thought that pre-Christian gnosticism was an influence. He “detected behind Hebrews the gnostic motif of the heavenly pilgrimage of the self from the enslaving world of matter to the heavenly world of spirit” and “identified the motif of pilgrimage as central to the development of Hebrews.” [Lane 1991, cix] There are problems with this theory too, among which is the lateness relative to Hebrews of the documentary sources Kasemann uses to establish his theory (e.g. Acts of Thomas).

Table of Contents

What if we did not have Hebrews? What would be lost? According to Richard Moore [1994, 333]:

Hebrews makes several major, indeed unique, contributions to the theology of the NT:

(1) It is the only NT writing to make specific mention of Jesus as a priest or (more accurately) high priest;

(2) It is the only NT writing to address the issue of the ceremonial law which occupies such a prominent place in the Jewish Scriptures.

What if Hebrews was the only book we had? What kind of theology could we construct?

- God speaks to us

“God, having in the past spoken to the fathers through the prophets at many times and in various ways ...”

- He has a Son, Jesus Christ

“has at the end of these days spoken to us by his Son ...”

- He is generous

“whom he appointed heir of all things ...”

- He created all things (through his Son)

“through whom also he made the worlds.”

- He calls his Son “God”

“But of the Son he says, "Your throne, O God, is forever and ever.”

- He testifies to the truth of salvation through the Son

“God also testifying with them, both by signs and wonders, by various works of power, and by gifts of the Holy Spirit, according to his own will ...”

- He has power-sharing plans for redeemed humanity

“For he didn't subject the world to come, of which we speak, to angels. But one has somewhere testified, saying, "What is man, that you think of him? Or the son of man, that you care for him? You made him a little lower than the angels. You crowned him with glory and honor. You have put all things in subjection under his feet."”

- He takes the initiative in redeeming humanity